Lakota: A Playboy Conversation with Frank Waln

published: Oct. 26, 2015

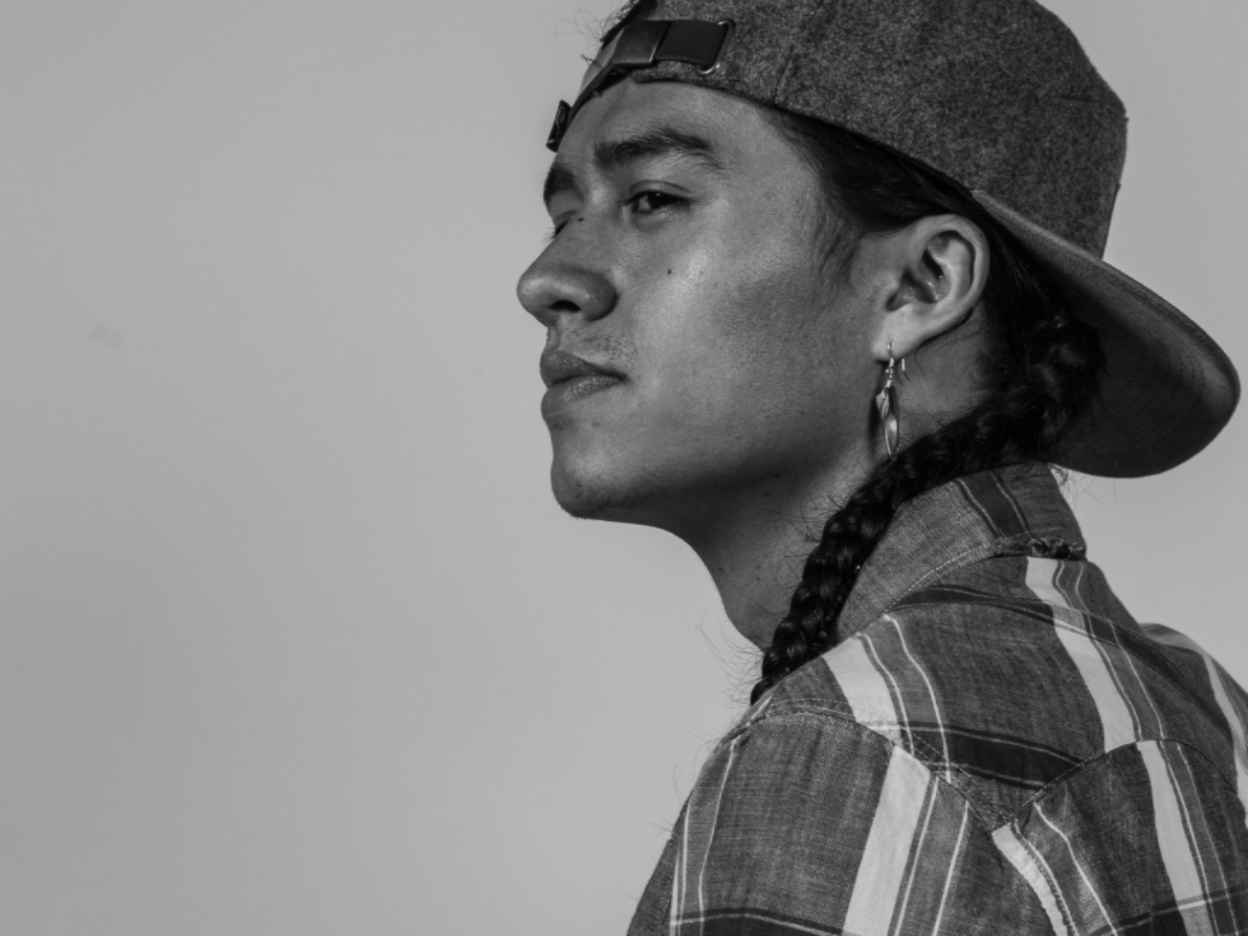

You may not know the name Frank Waln. I could tell you that he’s a 26-year old Sicangu Lakota rapper from the Rosebud Sioux Reservation. I could tell you that he’s an award-winning artist, a globe-trotting emcee and producer. I could tell you that he’s a Native-American leader and activist who’s been integral in the struggle to stop the Keystone XL Pipeline from risking the health of his people. But let’s reframe how we think about this young man. Because he is something new.

In “Radiant Child,” an essay about the New York art world in the 1980s, which considered the rise of the young painters Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, art critic Rene Ricard wrote: When you first see a new picture you are very careful because you may be staring at van Gogh’s ear. We often overlook newness because we don’t know how to see it. We must overcome our cultural biases and blindspots. Similar to how Basquiat moved from bombing street art into the white world of galleries, Waln is a Native-American man who’s moved into the ostensibly black world of hip-hop. Naturally, there are parallells.

Later on in his essay, Ricard wrote:

To Whites every Black holds a potential knife behind the back, and to every Black the White is concealing a whip. We were born into this dialogue and to deny it is fatuous. Our responsibility is to overcome the sins and fears of our ancestors and drop the whip, drop the knife.

We are born into stories. All of us. We must learn to address the sins of the past so that we can break and transcend those cycles of trauma and abuse. These are the sorts of messages we find in art worth talking about. And, just like with a new painting, when you first hear a new musician you don’t want to miss something important; you might be listening to Bob Marley’s echo.

Naturally, I’m hesitant to compare Frank Waln to the legendary reggae singer. Marley was undeniably unique. As the poets warn us, lazy comparisons are odious. But in this one case, the analogy is necessary. Much like Marley, here is a musician who uses his artistic gifts to heal. Frank Waln is one of those rare artists who puts his heart into his art, which gives it real power and an intimacy.

When you listen to his rhymes, Waln raps in cadences that boast a percussive power. His voice hits you square in the chest. His lyrics entertain your mind with stories from his life and of his people. He crafts his bars to be honest. His beats are thick. The result is catchy in a way that his music stays with you long after the song ends. Waln makes damn good Native American hip-hop. Which he hopes will help heal the world. Why? Because this is his world. This is the place where everyone he loves lives.

Waln sat down for an interview with Playboy, and he spoke with us about his music, about being a Lakota emcee, why love is the most powerful force in the universe, why he’s involved in the fight against the Keystone XL pipeline and about how he balances the dangers of creating “poverty porn” with the need for Indigenous people to tell their own stories to a nation that often relegates them to the past.

I’ve read that your love of hip-hop began when you were a kid; one day you took a walk and you discovered a discarded Eminem CD lying on the side of the road. Is Eminem why you decided to devote your life to music?

That was my first spark in hip-hop. But when I was seven or eight, I fell in love with playing piano. I started teaching myself how to play keys. So, I would say, my dedication to music started at the piano when I was seven or eight. Eminem was my introduction to hip-hop. But then, when I heard the Nas song “One Mic” that’s when I decided I wanted to be a rapper. That’s really when I devoted myself to hip-hop.

You attended Creighton University as a pre-med student. You’ve said that you wanted to do what you could to help your people. Do you feel music is a more direct form of healing?

My grandfather helped bring health care to our reservation. He helped organize a mobile clinic that traveled from community to community. We lived in very rural areas. Seeing that - how he helped heal people - I always wanted to do that. When I got my scholarship, it was like this golden ticket. Where I’m from, not many people get the opportunity to go to college. So, I was like, “Alright ,I have this scholarship. I’m going to go to college. I want to help people, I want to heal people. I’ll try being a doctor. I’ll try sports medicine because I also love playing sports.” I was in pre-med for two years. And I just kinda got burned out. I realized it wasn’t for me. It wasn’t in my heart. That’s when I decided to follow what was really in my heart, which was music. The summer after my sophomore year at Creighton was finished, I was talking to an elder back home. He was asking me what I was doing. I told him I’d left Creighton and that I didn’t want to do that anymore - I want to follow music. He kind of looked at me. He shook his head. And then he said, “Sometimes, music is the best medicine.” That quote stuck with me to this day. Music works for me, it’s how I heal.

Hip-hop was born from oppression. It’s often a music of protest. Hip-hop is also largely viewed as a young black artform. As a Native-American rapper, were you at all intimidated to step into the game? Did it ever feel like Eminem gave you license to think you could make hip-hop even though you weren’t a young black man growing up in a city?

That never even crossed my mind. Hip-hop resonates with a lot of people of my generation, whether they be in a city or on a reservation. I was thinking about this a lot lately. When I was growing up, the representations of Natives that we saw on TV were nothing like what we were living. Nothing like our reality. It was always, like, these savage Indians of the past. Very stereotypical. The media we saw, the artwork that we saw, the images in mainstream media that we related to the most, were hip-hop. Those artists were telling stories that definitely related to things we were going through, and are going through on the reservation.

When I started to listen to hip-hop, for the first time in my life I felt like someone was telling my story. Even though on a reservation it was a slightly different flavor, the circumstances that hip-hop was born into were the circumstances we were living in. So, a lot of Native kids from my reservation, we started making hip-hop. We wanted to be rappers. We wanted to express ourselves. This black culture gave us an inlet for us to rediscover who we are, to look at ourselves, and our own Indigenous identity. It was a catalyst for me to reconnect to my own culture. Now, what I’m doing with my music is taking hip-hop and blending it with my own experiences of my culture to make this new, unique, third thing. It all goes back to how I felt that first time when I heard hip-hop.

You first started out by yourself. You made your own music in your basement studio. Did that sort of DIY isolation give you the time and place to find your voice? Did you have the time to get frustrated and work it out? Get through those moments of, “Damn, that’s not quite the beat I hear… but it’s almost there!”

No one has asked me that before. I lived on a reservation. Very rural. It was before the Internet really took off. Since I lived out in the country, I would help my family out on the ranch. But then when I fell in love with music, it was kind of this escape. I was a very introverted, shy kid. Music was a way for me to escape and find someplace safe. That’s not to say that my home wasn’t safe, or that I didn’t have a great family, but everyone on the reservation is going through it. Music gave me that needed escape from all that.

On the flipside, it was hard for me to find my own voice, because being raised in the Midwest, in South Dakota, in the middle of the country, we had influences from all over. I was raised on old-school country music, and Fleetwood Mac, and CCR. My older cousins were listening to Mac Dre, Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, all that stuff from the West Coast, and from the South, and they listened to Bone Thugs. They also listened to stuff from New York. So, we were at this musical crossroads. It definitely took me about three or four years to take all those influences and properly package them into the music I’m creating. Now, all my influences make for some pretty unique music.

This one’s for the hip-hop heads. Who would you say is the Greatest of All Time?

Oh my god, the greatest of all-time? Okay, man, I’m gonna have to go with a group. For their uniqueness. And I love that they had their own production team. They’re one of my biggest influences: I would have to say Outkast. I really love Outkast. The first time I ever heard Outkast, I’d never been to Atlanta in my life, but their music it made me feel like I was in Atlanta. Like, I knew what it felt like. I knew what it tasted like. I knew what it smelled like. It just puts you in that place. I really appreciated that and I feel like that’s what I’m striving to do with my music.

As someone who grew up in Atlanta, you are 100 percent correct about Outkast. Okay, so, if they’re the GOAT, what new music are you listening to these days?

For the last year I’ve been into this group out of LA called Chicano Batman. A lot of their songs are in Spanish, and I don’t speak Spanish. I don’t really know what they’re saying. But I feel what they’re saying. It’s very beautiful music. When it comes to the hip-hop, I love TDE(Top Dawg Entertainment), all their artists (Kendrick Lamar, Schoolboy Q, Jay Rock, Ab Soul), like, their output is crazy. I’ve been listening to Future’s Dirty Sprite 2, a lot lately. I jam some Young Thug. As far as Indigenous artists, I always listen to Tall Paul. He’s an emcee out of Minnesota. He’s probably my favorite Indigenous emcee in the US, right now.

Dreaming out loud: Who would you love to do a collaboration with?

This is like the golden question. I’m always torn. But I would probably have to say Frank Ocean. I love him as a songwriter. I love him as a storyteller in music. I just love how he approaches creating music and creating art. I feel like we would vibe. And we also have the same first name. (laughs)

You work as both an artist and an activist. You’re very involved as a leader in the struggle to increase Indigenous awareness, as well as the fight for the cause of greater social justice. What pushes you to work so tirelessly for your people and for all oppressed people of the world?

I’m gonna reframe it this way and say: What I’m doing - the ideology and worldview that I’m using to approach what I do - is older than the word and concept of an “activist.” I’m just Lakota. That’s why I care about my people. That’s why I care about the earth. That’s why I care about the water. That’s why I care about my community. That’s why I care about people around me. That’s why I devote my gift of music and why I use my platform to protect those things. Because I am Lakota. That’s how I was raised by mother, and my aunties, and my community. That’s what I’m taught in my culture and in my ceremonies. A lot of time Native people get pinned as activists, but really we’re just being Native. I’m just living my life, and trying to live my life in a way that my ancestors and elders and my parents and my culture raised me.

It was announced that TransCanada wants to suspend its permit to build the highly controversial Keystone XL pipeline. The continent-spanning oil pipeline was planned to cross the Ogallala aquifer that’s integral to the water systems of the heartland of America. Your song “Oil for Blood” is about the Keystone pipeline, and about how the tar sands that are being carved out of Indigenous lands. You’ve been very involved in the fight against the pipeline. How does it feel to enjoy what looks to be a major victory against Big Oil, or at least, a battle won?

I tell people, when I perform: Where I’m from we don’t have the privilege to ignore this pipeline. We don’t have the privilege to ignore things like natural energy extraction. It’s our home. It’s outside of our front door. If this pipeline gets built, the water, the land, the health of me and everyone I love is at risk. Like, every day I wake up I think about that fucking pipeline. Not because I choose to but because I don’t have the privilege not to.

We’ve been resisting this pipeline for many years now. It’s great that it’s getting national attention now. One thing I’ve learned is that when it comes to the people making the decisions such as - Is this pipeline going to be built? - they don’t care about humanity. They don’t care about the earth. They don’t care about the soil or water. What they care about is money.

Whenever you can get small little victories like suspending this permit, or pushing back a construction date, it’s kind of like chipping away at the beast. You’re hurting their pocketbook. Every small victory is a great step forward for us, but we also know that it’s not over. From all the way up in Canada to way down into Texas, that pipeline is planned to pass over Indigenous land. The battle for us isn’t over, not until our relatives from the north and the south are guaranteed to be safe and healthy. It’s a great small victory because it gives me hope that what we’re doing is working, and it’s having an impact.

You’ve said that museums tend to perpetuate the view that Native Americans are a people of the past. But, as you are also quick to point out: Natives are very much of this moment. You “are a people with a past, not of the past.” Why do you think this cultural blindspot persists? Why do Americans tend to think/talk about Natives in terms of the past and not the present or the future?

I think because it’s so ingrained in the American psyche to erase Natives out of our conscious and put them in the past. That’s what they teach you in the history books. But now, after hundreds of years of erasure, thanks to social media and the Internet, we’re able to get more and more of our voices out there. Indigenous people are telling our own story. People are able to see a counter to the narrative. I think it’s so easy for people to dismiss us as part of history because this settler state, this country of America, it’s built on the destruction and erasure of the Indigenous people. Every day we wake up, we live and operate in a system built on that.

Native Americans often will speak of the Mohawk’s “Seventh Generation prophecy.” Do you find it interesting that social media is connecting young people of oppressed culture all around the world as the prophecy predicted?

I think it’s incredible. I’ve been thinking about this concept a lot lately. I can only speak for Indigenous people. When they put us on reservations, they confined us to a space. A lot of our tribes were very nomadic. We migrated with the seasons. We traveled in a way that we traded with each other and shared knowledge and stories. There were many lines of communication between all the tribes of United States and Canada, and all of South and Central America.

When they colonized us, they put us on reservations in order to cut off those lines of communication. They confined us. Now, poverty and this system keeps us in those spaces. But when the Internet and social media came around, it gave us this tool to reconnect and to reestablish all those old lines of communication.

I think for Indigenous folks, the Indians all across Turtle Island, really gravitate to social media because it gives us a powerful tool to reconnect inter-tribally. We can share knowledge and stories and information. And we’re also using it as a tool to organize. We’re using it as a tool of resistance. I think all of that plays into the prophecy of the Seventh Generation. There are many things I’m seeing in my lifetime that are showing how that prophecy is coming true. At least, I believe.

You’ve had a painful past with your father. You grew up in a single-parent household. Yet, you’ve turned your anger into something positive so that it doesn’t destroy you, and you don’t repeat your father’s mistakes. Do you feel like you’re trying to reach out a musical hand to help and inspire other young Native men so they can also escape those cycles of violence and self-destruction?

Music was the outlet that I needed. I think art is a great outlet to express our anger, our frustration, our pain. We’re dealing with 500 years of genocide and the colonization of Native people. We’re born with historical trauma in our DNA. Our ancestors survived genocide. We’re not even supposed to be here. This country tried to wipe us out. We’re born into all of that. The things that we go through in communities that are built on that destruction results in a lot of anger, pain and frustration. I think hip-hop, for me anyway, it gave me a good outlet to get all of that out, because you can’t keep that all in as a human being. It’ll eat you alive.

Also, I don’t agree with people when - white people, basically - say, “Don’t be angry. Don’t be frustrated.” I used to catch that early on when I started expressing my anger in my music. People would say, “Why are you so angry?” Even Native people would say that it made them uncomfortable. I would say, “Well, I’m a human being. And if I want to feel these feelings that result from 500 years of colonization and genocide, I can. I’m sorry if my humanity makes you uncomfortable.”

We have the right to feel our anger, our pain and frustration. I’ve found in my own life - I’m not perfect, at all - I’ve messed up many times where it comes out in ways that we hurt people, the ones that love us. Music and writing music, and performing music, it gave me a way to get that anger out of me. In a healthy way. I encourage people - especially, Native men - to find that outlet. Find that healthy way to express yourself. It helped save my life.

Being raised by the women of your family - how do Native women inspire you? What lessons did they impart to you that shaped who you’ve become?

I’ll try to keep this one short because I could just go on for days about them. Everything that I do as an artist, as a person, every quality that I have that has led to my success, is due to how I was raised. Because of my grandma, and my aunties, and my mom. The type of people they are. They taught me that love is the most powerful force in the universe.

I’ve seen some crazy-ass things, man. And I’ve seen love get my family through those crazy-ass things. I’ve seen love get people through things you wouldn’t think anyone could get through and be happy through it, or smile through it, or laugh through it, or create through it. And you know, here I am a young Indigenous person from Rosebud Rez who gets to travel the world and do what he loves, and also I get to share my stories from home with the world. I feel really blessed and really privileged. It’s all because of how they raised me. How they taught me to love. How they taught me to take care of the people and things that I love.

The First Nation communities are still often blighted with poverty due to centuries of economic violence and the theft of their land. You’ve said that you have to avoid the trap of telling stories that are essentially “poverty porn.” Is it difficult to talk honestly about the troubles of your community since you have to worry about how others outside the community perceive and use what you say?

I wouldn’t say it makes it difficult. It just makes me conscious of how I tell my stories. Where I’m from, poverty is definitely a huge problem. But I think those are our stories to tell. When I see stories about poverty on the reservation, it’s usually non-Native people telling those stories. I think that’s where it goes wrong. They don’t see all the factors, not the way that your question did. And they also miss the hopeful side of things.

I don’t shy away from telling those stories or expressing those things about my community. It’s the truth, and to pretend otherwise would be a disservice to myself and my community. We need to work on those things. And I just make sure I balance it with hope, with some light and positivity. I’m careful to supply hope when I talk about those negative things like poverty.

What’s next for Frank Waln? Both as an activist and as an artist? And I mean, as a Lakota.

I have a ton of upcoming shows; I’m booked through the spring. I just came back from Paris. And I’m gonna go back to Paris in December. I’m also going to Germany and Liverpool in 2016. But what I’m really excited about is that I’m working on an album right now. It’s called Tokiya, which is a Lakota word for firstborn, or the first of its kind, you know. It’s me telling my story of being a young Lakota person from a reservation in South Dakota. And it’s actually the story of healing.

We’ve touched on that throughout this interview. When the settlers came and colonized my people, they needed to cut us off from our connection to our culture, to the land and the earth, to our ceremonies, to our ancestors, to all the things that gave us power and told us who we are. My generation is living in the time of the aftermath of that.

This album is my story of how I heal those disconnections, and how I reestablish those connections. For me, personally, at least. Working through all that historical trauma and pain and frustration that I’ve experienced, and I’m still going through it, man. So, you know, I’m telling that story.

I’m getting to collaborate with a lot of really dope artists that I’ve been able to meet now that I’m able to travel all over the world. But I’m very critical. It’s really rare that I impress myself with anything that I’ve made. I look at the stuff I have out now and I feel like, “Oh god, I could do better.” This album… it’s the first time I’ve ever been this proud of something I’ve created. It’s definitely on another level. I’m excited to give this one to the world.

Word. When can we expect this new album?

I like to say that I’m Native, so I don’t like to announce hard dates. (laughs) I like to go by seasons. So, I’m looking to put it out in the winter.