Inclusive and Introspective Theater

Spring 2021

Theater artists Brian Balcom and Tsehaye Geralyn Hébert talk with writer and educator Anita Gonzalez about possibilities with technology and becoming the people with “buy-in” to making changes and greater accessibility.

This is a transcript of the closed captions from the video conversation.

Anita Gonzalez: Today, I'm in conversation with two artists who participated in the 3Arts Residency Fellowships at the University of Illinois at Chicago. This is part of a series of conversations designed to promote the art of Deaf and disabled artists and their experiences in that fellowship program.

Brian Balcom is a theater director and accessibility advocate who's produced and directed several contemporary plays at theaters throughout Chicago, Minneapolis, and beyond.

Tsehaye Geralyn Hébert is a citizen playwright and accessibility advocate whose work draws upon African-Creole culture, often centering race, gender, disability, and the economics and geography of making art.

Brian Balcom: I primarily focus on contemporary, narrative based and muscular theater. I love stories where people are fighting against seemingly insurmountable odds. Fighting against a conflict that seems insurmountable and finding a way to navigate that or wrestle with that. And as far as what I do administratively, I am a proponent of access for all. Eliminating any physical, any language barriers, any barriers to participation. And that also comes in storytelling too, making sure that the story is accessible because we're here to create empathy. We're here to reach out to different people and different audiences and trying to change their minds one way or the other, to get them to to see things in a different way.

Tsehaye Geralyn Hébert: My work is more hybrid. Opening doors and windows to excavate a story, so to speak, and to discover as you're going along, what the poetry in that story is. I'm really involved in legacy right now and history. The part about inclusion that is so extraordinary is that it gives us so many tools to tell a story. I come from a place where different languages were spoken and, as we speak, my Creole language is fading every day and with it, a bevy of stories. To hear those stories in their native tongues and to understand what place might mean or not mean. It's about excavating a lot of ideas and if the inclusion is a part of the value at the beginning of writing that script, it continues to unfold. I have noticed that, if it comes in at the end, it's prescriptive and it kind of sits on top of things, almost like, "Let's put this ornament here. Oh, look, we have this." I'm really taken by the hybridity when we're making pieces and making work and collaborating and bringing in different styles, different languages, different systems and how that works together. That excites me.

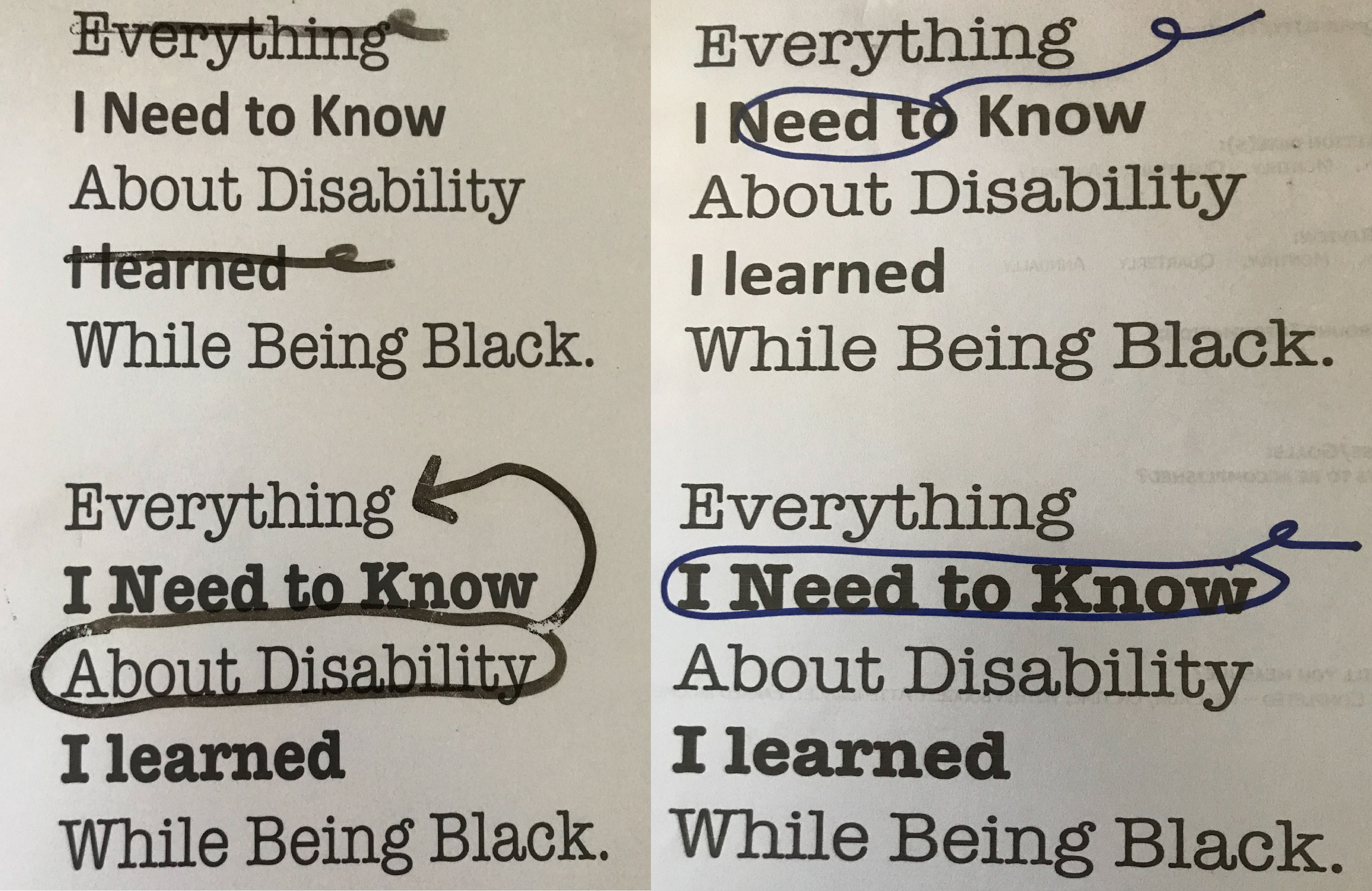

Everything I Need to Know. Tsehaye Geralyn Hébert

Everything I Need to Know. Tsehaye Geralyn HébertAnita: That's beautiful. I love these images that are at the core of the work that each of you do. Tell me about Chicago. What does it mean to you to be a part of the Chicago disability arts community?

Tsehaye: I would say it has been challenging and also freeing to just have inclusion as a value, as content, as structure, as infrastructure, as theory, as praxis. It is very exciting for me. And I think, because that can be unfettered, it has allowed me to think so far beyond the box. It's certainly fed into the hybridity and the collaborative process that I find really, really exciting.

Brian: I think for the first time in my life, I have felt embraced and I have felt supported by a community.

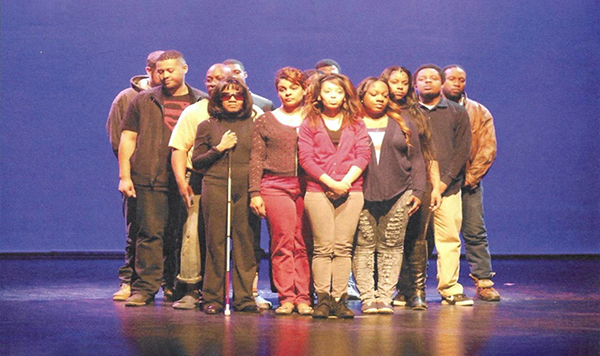

Fast Company, Theater Mu. Directed by Brian Balcom

Fast Company, Theater Mu. Directed by Brian BalcomBrian: It's only been in the last five or six years that I have really sort of embraced my identity as a disabled person, as a disabled artist and not that I was refusing it or rejecting it before, but I hadn't yet really embraced it and now that I own that part of my identity or I'm working to better own it. All these doors have opened and I don't just mean opportunities, but relationships and a sense of belonging. I think there are still challenges. There are still things that we are fighting for and against, but finally, I am included in something larger than myself which has been great.

Anita: I really appreciated how when you were talking about what drives your work, you talked about accessibility in many different forms that were part of the way that you envisioned how your work should be situated. Have you faced any challenges in promoting that vision of accessibility in Chicago or in other aspects?

Brian: Yes, I have, and you know, it has taken multiple different forms. It feels like I am restricted to only working with theater companies that have accessible spaces, both onstage and backstage. Because of the nonprofit nature of what we're doing, companies, organizations, find spaces wherever and whenever they can for as little money, sometimes, as they're able to afford, and that means working in older buildings that means working in inaccessible buildings. It's tricky to navigate things like that, to decide who do I build relationships with. Who might be open to such a thing? That's a lot of financial burden to ask an institution to do, especially if their budget is at a certain level. Physical access for me is the biggest challenge and actually, you know, having the opportunity to do work.

Brian: On the administrative side, buy-in is a big challenge, buy-in from leadership, from artistic directors, from executive directors, from boards of directors to say, yes, this is important for our community. This is important for the institution, to lead in this way and to make these offerings for our audience.

Anita: I'm very grateful for having you as an advocate, but I know it must become tired doing all the time, right? I mean, that's where the community comes in there's a community to lean on when you get exhausted, right, from the constant advocacy that you have to do just to assure yourself the place to be able to do your artistry.

Meditation. Tsehaye Geralyn Hébert

Meditation. Tsehaye Geralyn HébertTsehaye: Everybody has learned something because we've learned it by doing it as opposed to saying we don't have any money, we don't have any staff, we don't have any time, we have no know-how. We know that going in, but maybe I'm the village idiot that wants to go in with that blue sky vision first and say, I can bring this down to Earth, if you will, but what does an ideal look like? Because we're not even thinking about what's the ideal setup for a person to have access to the stage. So I think; how do we think about disability and access and inclusion is radical for some people when we're simply asking to be able to get through the door. It's not going to change until I participate in that change with others in collaboration.

Anita: Everyone would like to see it in process and product but they don't always want to see it in the bricks and mortar of the edifices that we work in and also in the actual budget. What does it take to make sure accessibility is real to people? That's the question that keeps popping up for me.

Tsehaye: I think in five years, maybe we, don't have to worry about how to get the ASL interpreter. Maybe we don't have to figure out how to make the piece audio described. Maybe we've got that taken care of and when I say taken care of, I'm not just talking about the technology because technology is changing

Tsehaye: When people talk about technology and PWDs, people with disabilities, they act as if we're still trying to figure out how to use an electric can opener, when most PWDs have been so far ahead of the TQ, the technology quotient, that we're showing other people how how to do it. So that makes us end users, brilliant end users, in understanding how systems work, because we understand how systems didn't work for us.

Brian:I think your point about technology is is exciting as far as integrating access into what we do whether it be something like, you know, glasses that we wear that display captions on them or virtual reality. I think especially for people who have difficulty leaving their homes, I think virtual reality is a really exciting development. And if we can figure out how to make it feel like you are sitting in a theater, surrounded by your peers, I think that's really exciting. And also, you know, just seeing what has happened in the last year with the lockdowns. I was fortunate to have a show, the last show I did, our opening night was the last day before everything got locked down but we were able to put it online and we had people tuning in from all over the country and all over the world. So, just that access, I think, online programming, I hope, is here to stay in some form and in another with theaters. I'm excited to see where technology, to your point, will take us as far as access to art.

Vietgone, American Stage. Directed by Brian Balcom

Vietgone, American Stage. Directed by Brian Balcom Anita: I want to know what does the 3Arts Residency Fellowships mean to you?

Brian: My fellowship was split up into two areas. One was, you know, doing a lot of research and reading of playwrights who identified as disabled and the other part was mentorship with a handful of artistic directors in town.

Brian: My hope is that I don't have to fight for buy-in anymore from top down. I can be the person that buys us in, to say these are the things that are important. These are the things we're going to offer. These are the stories we're going to tell. Be that leader to make those choices for an organization in the community.

Teenage Dick, Theater Wit. Directed by Brian Balcom

Teenage Dick, Theater Wit. Directed by Brian BalcomTsehaye: I would like to use the word catalytic because just the opportunity to have the time, the space, the funding to devote to reading more about Disability Culture. I came to disability as an embodied experience later in life, but I grew up in a disability rich world. But I think it's not until you look into, or begin to conceive work that you start to think about how to broaden the scope of that work. So that it's more open and it's not closed.

Tsehaye: I think working with 3Arts really continued a fundamental shifts in my work. Like the first time I worked with ASL, I'd never went back to not integrating different aspects of language.

The C.A. Lyons Project. Tsehaye Geralyn Hébert

The C.A. Lyons Project. Tsehaye Geralyn HébertTsehaye: I worked with a sculptor and there's this 12-foot sculpture and there's this incredible detailed frieze across the top of this obelisk and there are scenes from the Civil War. I kept thinking, well, if I was in my wheelchair, I wouldn't be able to see that. That's a shame. So in playing with the idea, the sculptor started to brainstorm with me about how I could bring the obelisk into the audience. Why don't you build the sculpture as a light box and project it and bring that out over the audience. I was like, wait a minute, can we do that? So there was this moment where the light bulb went off. It was like, who said you couldn't? I don't think I would have thought about that, had the designer not begun to create a 3D structure and then we were just doing this round robin and at the end of the process, it was completely different than what I came in there with this little thought and then it just went poof. And I think that's the value of time and talent on an idea.

Anita: Those are wonderful answers. Thank you so much. It's been amazing to hear about all of your work and also about all of your advocacy, because I love when it's embedded in the work that we actually do is advocacy for the things that we believe in. So, I'm going to bring us to a close and thank you both for being here.

The Disability Culture Leadership Initiative and 3Arts/Bodies of Work Residency Program are supported in part by grants from

the Joyce Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.